In this section

In this sectionShould organisations working to promote clean cooking solutions in displacement settings focus on only solar electric cooking? What is the most cost-effective way to provide electricity access to households living in refugee camps?

At a workshop co-hosted by the IKEA Foundation at its office in Leiden, the Netherlands, we asked some hard questions to a group of donors and partners working on energy access for displacement-affected communities in East Africa. Our goal was to identify nuanced approaches to address some big challenges when it comes to enhancing sustainable energy access in refugee camps and settlements in Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda.

To do so, we presented the workshop participants with opposing views and asked the participants to position themselves on a spectrum – both theoretically and physically around the room – according to how much they agreed with it. This is what our participants thought about the following questions:

Electricity or improved biomass for cooking?

The vast majority of households in displacement settings in Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda cook with firewood or charcoal over mud stoves or three-stone fires. This is harmful both to people’s health and the local environment through deforestation. Electric cooking (powered either by the grid, a mini-grid or a solar unit) can be a more cost-effective cooking solution in the long run whilst providing health and environment benefits. Pilot projects – such as the PEPCI-K project in Kakuma in Kenya and the Pesitho-Mercy Corps collaboration in Bidibidi refugee settlement in Uganda – have shown promising results, offering cost and time savings as well as being compatible with local food, but have reached only a fraction of the people in need of clean cooking solutions.

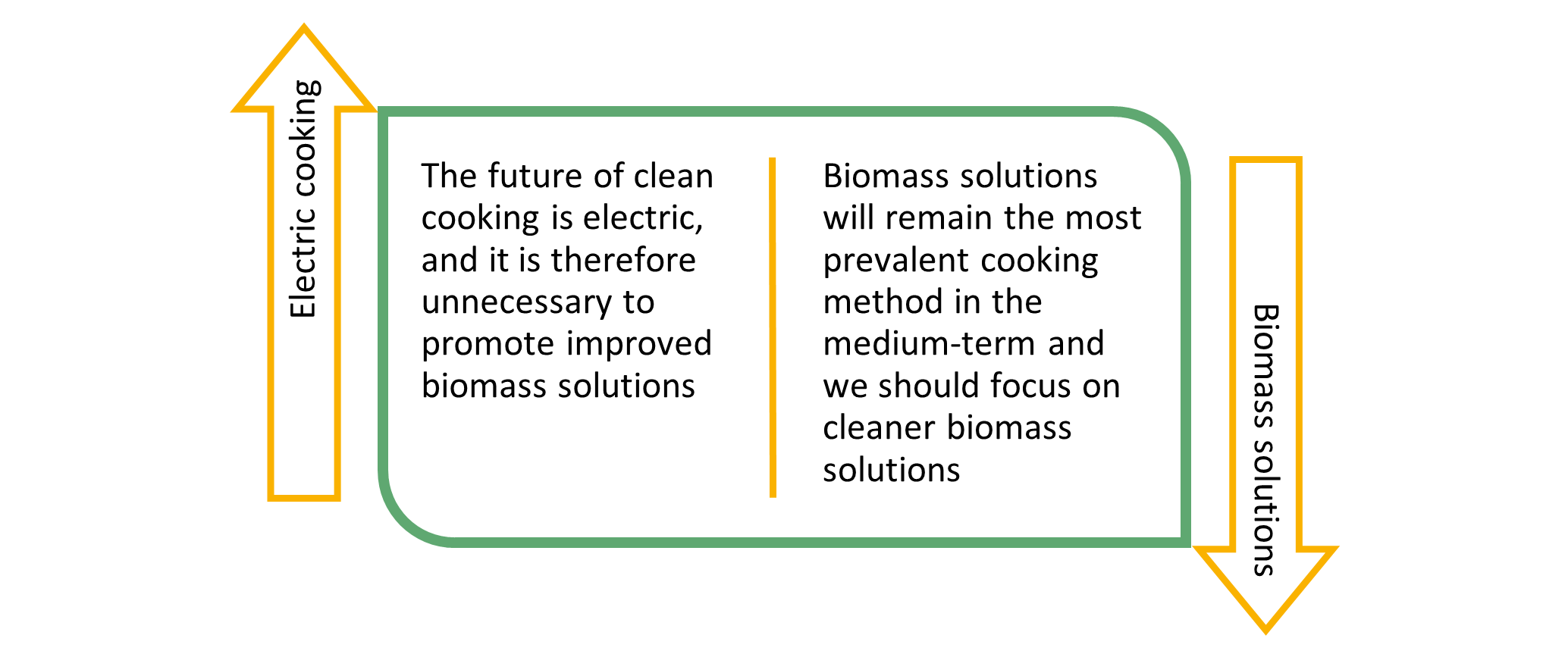

We wanted to know if the workshop participants thought that efforts to promote clean cooking should focus on promoting and building markets for electric cooking or on improving biomass solutions, given how they are likely to remain the prevalent cooking technology for the foreseeable future. Participants in favour of predominantly focusing on e-cooking emphasised the health and environmental benefits (both in terms of climate change mitigation and reducing local deforestation), highlighting opportunities to leverage carbon finance.

Arguments in favour of focusing on improving biomass solutions were the benefits of enhancing a method that is already widespread, familiar, and accepted, as opposed to a solution for which uptake might be slow, given high upfront costs. They also emphasised that there are tested and relatively easy methods to increase the efficiency of biomass solutions.

Participants recognised that the “endgame” will likely consist of a mix of cooking types. For that reason, they recommended building markets for not just one but rather a variety of cooking solutions, saying that efforts should focus on making each technology cleaner, more efficient, and more affordable. Various strategies to transition away from biomass within different timeframes were discussed, with mixed opinions on if LPG had a transitional role to play. Participants also said that good coordination of interventions promoting different technologies is key to avoiding disrupting market building efforts, that national policies often define which interventions are and are not possible, and that the involvement of communities in the design of interventions is essential.

Grid and mini-grids or solar off-grid solutions for electricity?

Most households in displacement settings in East Africa lack access to a reliable electricity source. Even refugee camps and settlements which are connected to the grid typically do not provide connections to households. Solar off-grid solutions (like solar home systems and solar lanterns) are becoming increasingly popular, thanks in part to efforts by organisations to promote their uptake.

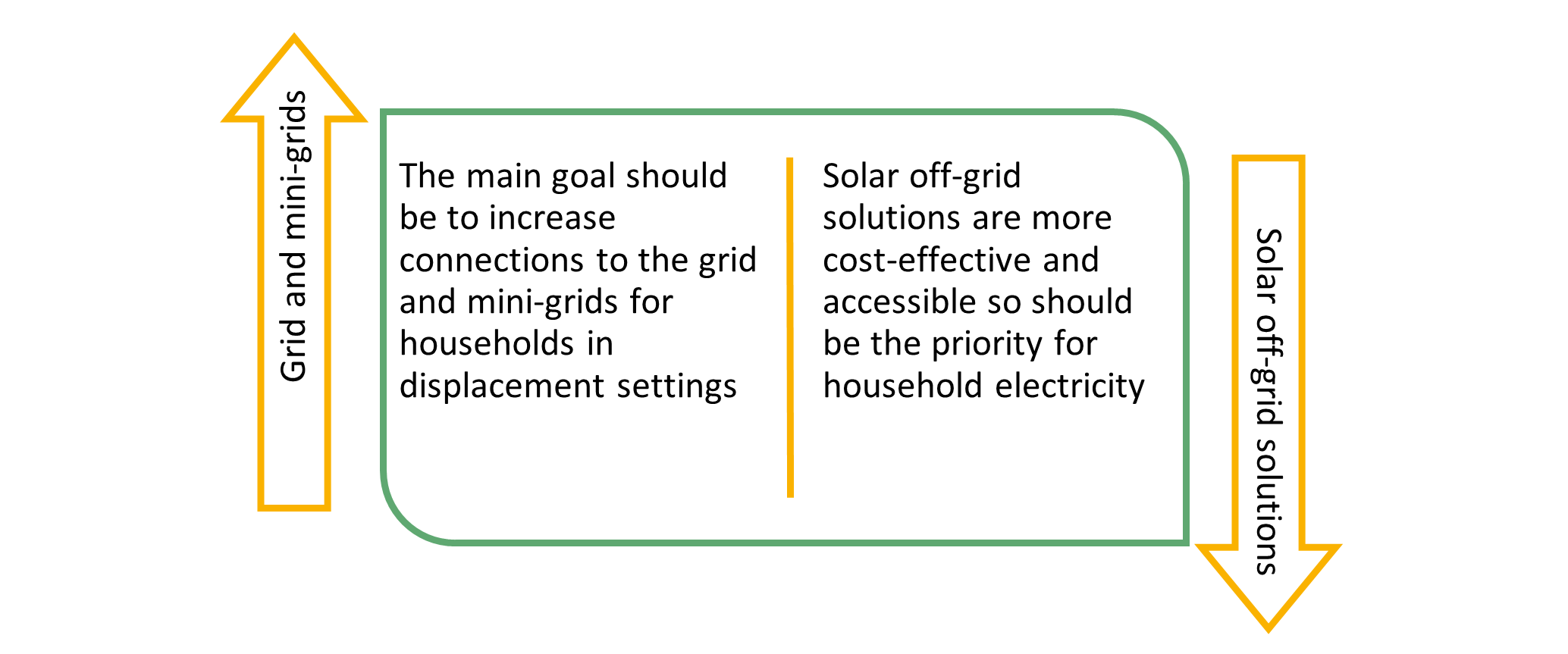

We asked our workshop participants if it would be better to focus on promoting connections to the grid or mini-grids for households in displacement settings, or instead to promote solar off-grid solutions as a more effective solution. The side of the room which favoured grid and mini-grid connections highlighted the benefits of economies of scale and the ability to respond to different types of demand. They also stressed the importance of including displacement-affected communities in national electrification policies.

On the other side of the room, arguments in favour of off-grid solar solutions emphasised the infrastructure and practical challenges associated with facilitating grid or mini-grid connections in remote settlements including safety concerns with connecting shelters. They also argued that mini-grids are rarely commercially viable even in non-displacement settings, highlighting that they typically have to be highly subsidised.

Interestingly, when asked to reposition themselves to what their organisation was working towards –as opposed to what participants personally thought – there was a shift towards solar off-grid solutions. Participants agreed that, regardless of the technology, electrification should be through least-cost pathways and compatible with government priorities.

Meeting in the middle?

Our workshop discussions clearly showed that it will be necessary to promote a variety of energy solutions to meet the immense energy needs of people living in displacement settings in East Africa. While it is important to build markets for transformative technologies like electric cooking and enable higher levels of electricity access through the expansion of the national grid, it is also crucial to recognise that these efforts will take time. People need solutions now and it will therefore remain imperative to make improved solutions, like more efficient biomass cooking technologies and solar off-grid solutions, more easily accessible and affordable.

Want to learn more? Download our workshop report here to read out the other important discussions on donor priorities, reflections on key issues, and actions for the future.

Find out more about the READS Programme here and its work in East Africa here, or download the READS Kenya report, Rwanda report, and Uganda report.

Last updated: 27/02/2024